– Sofia Rodrigues Bolina

I come from strawberry jam and bolinho-de-chuva. From a fabric doll and a snow globe that plays the theme song from “Beauty and the beast”.

I come from a refusal of ever letting me believe in Santa Claus and the Easter bunny, from a tradition of eating popcorn with ketchup. I’m from the one yellow hibiscus flower and the rosemary sprigs in my grandmothers’ gardens. Somewhere in the earth where rosemary (the plant) is rooted, where Rosemary (the aunt) used to play, lies the corpse of a chicken which tried to take a bite off my finger when I was two or three and clueless about the world. Rose (the grandma) finds the episode somewhat funny to this day.

I come from his love of talking through philosophical subjects and her practicality and devotion to showing she cares by cooking for others. I come from the curly hair in his head and his wide nose, his adoration of all things musical; I come from her straight hair and thin nose, her obsession with period movies and lying in a hammock by the sun.

I come from “Dreams from my father”. And from my mother’s dreams. And my father’s too. And from late-night dancing lessons followed by Italian ice-cream. And from a fertilized egg, an embryo.

I’m from a long line of unborn babies, the miracle that took seven years to come to life, and with me came also two other kind and brown-skinned beings after we celebrated my fourth and seventh years on Earth.

I’m from a family where no one ever refused to buy me a book, which is not really something said family had the privilege of doing when they were children. I come from a Black patriarch whose skin turned white and studied engineering, and a white one whose skin stayed white and worked at factories. I’m from a series of intense contradictions, so intense it took me decades to truly grasp.

I’m from a colonized land but also from the land of colonizers, where olive trees grow and Port wine is drunk and pretty tiles fill streets with color and people speak their Rs and Ss in a very funny and pronounced way. Just like Rose, the grandma, sometimes does.

I’m from a colonized land and yet I’m both from the Greek word for wisdom, sofia, and from the Kimbundu word banzo – the melancholy, the saudade, the depression and hopelessness of the enslaved whose specific colonized land I’m not really sure of.

I come from a place, down south, where the question “where do you come from?” is an opportunity to proudly introduce oneself as not originally being from this land of corruption. It’s a story of migration, but one about people who easily get red, not tanned, under the summer sun. It’s a “where do you come from?” that rarely hurts to get asked, because these people do have a precise answer – a sort of glamorous one, though the reality of nineteenth and twentieth century immigration wasn’t as glamorous as some of them make it seem. They know this answer because it’s in their surnames, the Schmidts, the Yamamotos, the Martinellis; they know it because their great-grandparents and grandparents remember what it felt like to set foot in the New World.

I come from a place, down south, where those whose skin tans like mine are almost never asked “where do you come from?”. Maybe it’s because people don’t want to be reminded that our real surnames were erased and that documents were burnt. Maybe it’s because we are so many now that it’s easy to assume we were never really brought here. It’s a story of migration out of a place we cannot pinpoint in the map, except for perhaps saying that it is probably somewhere in the west African coast. Benin or Nigeria or Ghana or Angola. It’s a story of migration I can only partly tell precisely, because only Rose, the grandma, remembers the boat that brought her – unchained, by her own will – from Portugal in the 1950s. Romeo, black-skinned turned white, and his Juliet, black-skinned who stayed black, don’t have any memory of that.

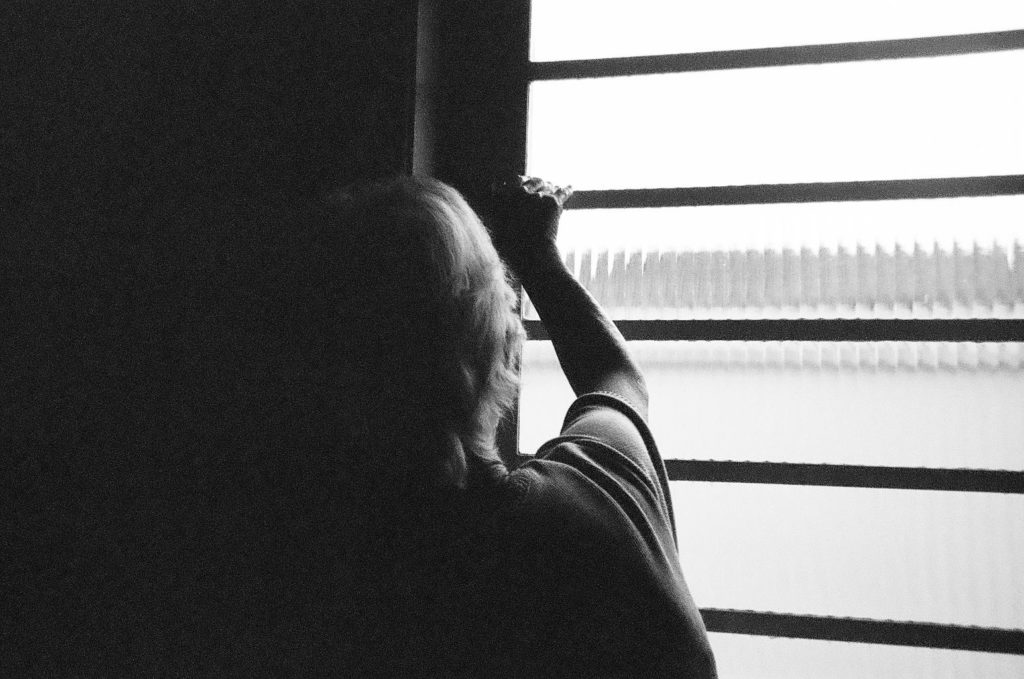

Now I’m in a place up north. A place where the question “where do you come from?” is an opportunity to dis-place someone – some other – for not originally being from this land of efficiency and potatoes and sausages. It’s a story of migration, but one about people who aren’t welcome and who, I imagine, must feel their blood boil when an overemphasized “really” is added to the question when they answer “from here”, “from Hamburg”, “from Prenzlauer Berg”. It’s a “But where do you really come from?” that often hurts to get asked, because these people already gave a precise answer – albeit not the one the inquiring want to hear. They expect something in the lines of “I come from tabbouleh, halloumi, gyros, jollof rice or pho”, because clearly the food, the delicious-and-now-easily-found-in-any-Großstadt food can stay. But it would be better if its people just didn’t.

In this place up north, from where I do not come, I now get asked that question often. It’s triggered by my looks, which make people link my brown-skinned face to somewhere in South Asia, the politics of passing in place so that one ascribes to me a heritage that isn’t mine. It’s triggered by my accent, my mis-choosing of der das die, or by the weird language I’m talking on the phone in line for a cup of coffee, or on the subway, or at a store. And so the Latin-derived words of the colonizer, which do not match the origins people assigned me just by looking at my complexion, make them confused and a bit surprised with my answer to that triggering and universally asked “where do you come from?”.

Some hear “I come from a tradition of living up in trees in the rainforest naked and speaking Spanish”.

Others understand something like “I come from a long line of bikini-clad women who act as if carnaval happened year-round and who don’t walk, but actually dance samba when they move through the city”.

What I really say is “I come from Brazil”. And it’s to those who simply listen to that, who don’t displace or misplace me, usually because they experience that too, to those who get my coming from strawberry jam and bolinho-de-chuva, from Romeos and Rosemaries and curls and ice creams and gardens and love and oh-so-many-things, to those who hear that, my not at all single story… to those, I’m truly grateful. Almost as much as I am for the resilience and idiosyncrasies and trajectories of those from whom I come from. To them, I say: thank you for making me come from somewhere and someone.

#origins

#migration

#colonialrelations